|

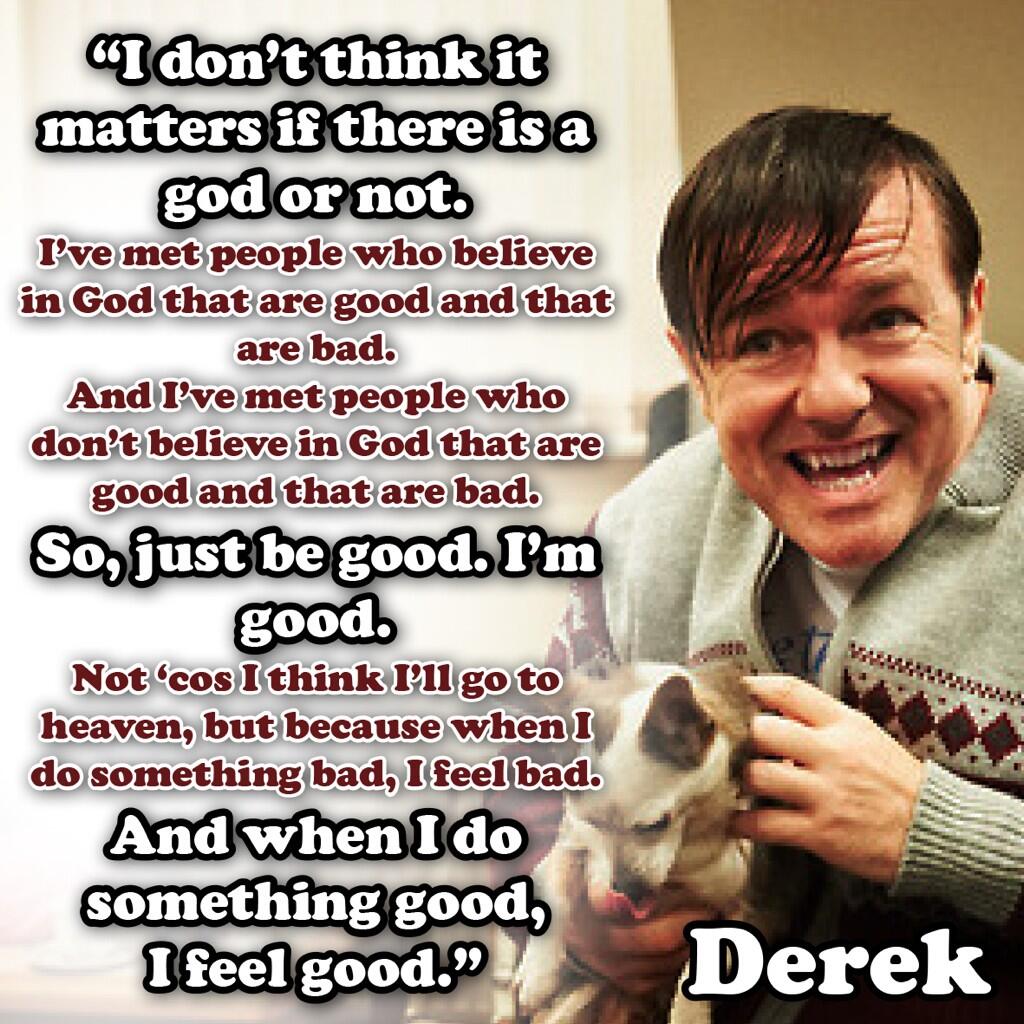

| Derek was a British television series starring Ricky Gervais. |

Derek says to be good, and I agree. How does one do that? By what standard does he measure his goodness?

Some New Atheists will rely on convoluted arguments to try to prove that man can have absolute morality (right and wrong) without an absolute source (God). One might suspect that the argument behind this meme is not quite so complicated. Ricky Gervais, whose character Derek gives us the sage advice to “just be good,” seems to be like so many average people who are de facto atheists; they say they don’t believe in an absolute system of right and wrong, but live as though they do. This standard of “good” which Derek calls his fellow man to live up to is supposed to be understood by all people. Indeed, I believe it is understood by all people; I simply disagree with the New Atheists regarding the reason why that is the case.

This is one of the problems with New Atheism that people don’t seem to want to acknowledge: We are supposed to accept the conflicting ideas that 1) there is no absolute truth or morality, decreed by God and built into mankind, and 2) everyone automatically knows what “good” is. For all the talk of the irresolvable paradoxes of Christianity, this problem of morality is significant for the New Atheists. If there is no absolute standard by which to judge morality, then all morality must be relative to the culture out of which it arises. Even if there are similarities between cultures, one cannot claim that there is an absolute standard. How, then, can one say that a given thought, word, or deed is good inter-culturally? How can one society apply its standard of “good” to another society, absent a universal standard? At least the Christian points to God, and says that He ultimately understands the religious paradoxes, if we cannot.

Or, looked at another way, how can we judge any given thought, word, or deed as “bad” if there is no absolute standard of morality? New Atheists like to point this out to Christians who condemn sin and call people to repentance and faith in Jesus Christ for the forgiveness of those sins; the point applies equally to them. And, contrary to how it may seem based on the circulation of internet memes, the New Atheists condemn quite a lot as bad. Christianity, for starters. Richard Dawkins believes it is child abuse to teach children the Christian faith;[1] so did the late Christopher Hitchens. In fact, they despise all religion as evil. This includes Islam.

Their hatred of religion made for some strange bedfellows during the war on terror. After the September 11th terrorist attacks on the World Trade Center some leftist atheists, like Christopher Hitchens, supported aggressive war against Muslims in Afghanistan and Iraq alongside the likes of, well, me. This was because terrorism is bad. The oppression, abuse, and subjugation of women is bad. Murdering political and religious minorities is bad. Oppressing and murdering homosexuals is bad. All these things are bad according to the New Atheists, and I agree. I must again, however, ask the question: by what standard? Clearly, the Islamic terrorists don’t think those things are bad. Why is their standard different? Where did it come from? Do they not have the innate sense of right and wrong, good and evil, which all men are supposed to have? Absent a universal standard of right and wrong, what makes them evil?

The Christian has an answer: the God who created the universe has set an immutable standard of right and wrong for mankind and expects us to keep it. We cannot. In fact, we ignore and suppress it. We turn away from God and His moral standard. We fail to keep it. And, when we do not keep it, that is called sin. And, because we cannot keep this moral standard perfectly, He took on human flesh in the person of Jesus of Nazareth, so that He could destroy sin, its inevitable result – death, and the one who brought it into the world – the devil, once and for all. He accomplished this by the death, resurrection, and ascension of Jesus Christ. He did it by living up to the standard, and dying as the sacrifice for sin on man’s behalf. Then, after dying on the cross, He rose up from the dead. We benefit from this sacrifice when we are brought to penitent faith in Christ for the forgiveness of our sins, by the power of the Holy Spirit, through the means of God’s Word and Sacraments. That is our explanation. What is theirs?

Their explanation for morality seems to be that morality has developed in man’s psyche as a product of evolution. The late Christopher Hitchens said:

I think our knowledge of right and wrong is innate in us. Religion gets its morality from humans. We know that we can’t get along if we permit perjury, theft, murder, rape. All societies at all times, well before the advent of monarchies have forbidden it. Socrates called it his daemon; it was his inner voice that stopped him when he was trying to take advantage of someone… Why don’t we just assume that we do have some internal compass?[2]

This view is almost comically simplistic. We just all should know what good is, because good comes from inside man. I see much evidence in man’s history that, far from being innately good, man is innately evil. Mr. Hitchens sets up this straw man: religion teaches that men only do good things, return lost property, give blood transfusion, etc., because they fear divine punishment and, if they didn’t have that threat hanging over them, they would act like the worst psychopathic criminal.[3] Perhaps other religions teach this idea; Christianity does not. In fact, Christianity teaches that, outwardly, and because of the conscience, men can and do live outwardly good and decent lives. Men can choose not to steal, rape, or murder their fellows, but this civil righteousness does nothing to justify a man before God. The Book of Concord has this to say on the issue:

Our churches teach that a person’s will has some freedom to choose civil righteousness and do things subject to reason. It has no power, without the Holy Spirit, to work the righteousness of God, that is spiritual righteousness… This is what Augustine says in his Hypogonosticon, Book III: We grant that all people have a free will. It is free as far as it has the judgment of reason…It is free only in works of this life, whether good or evil. Good I call those works that spring from the good in nature, such as [sic] willing to labor in the field, to eat and drink, to have a friend, to clothe oneself… For all of these things depend on the providence of God. They are from Hm and exist through Him. Works that are willing to worship an idol, to commit murder, and so forth, I call evil… Although nature is able in a certain way to do the outward work (for it is able to keep the hands from theft and murder), yet it cannot produce the inward motions, such as the fear of God, trust in God, chastity, patience, and so on.[4]

Christianity also teaches that this innate morality is objective and immutable, created by God. It is perfect, and requires perfection. And, no matter how many good deeds one may do, no matter how “good” a person may be in the eyes of the society, it is impossible to keep this moral standard perfectly, as God requires. Our relationship with God, therefore, must be repaired in some other way than by being good, or doing good deeds. On the contrary, our relationship with God is repaired by the death and resurrection of Jesus, who died as the propitiation for the sins of the world; and we receive those gifts of forgiveness and life eternal through the gift of faith, which God creates in us through the means of His word.

I see man, when left to determine what is right and wrong for himself, holding his neighbor to a separate, higher standard than the one to which he holds himself. This phenomenon manifests itself from the individual level to the societal level. The Godless [sic] principle that the strongest is always right has been openly declared as recently as the twentieth century in Mussolini’s Italy and operated in practice in Hitler’s Germany, Stalin’s Soviet Union, and many other states.[5] The evidence shows us that, unless man’s moral code is instituted by an authority higher than himself, he will, when it is advantageous to himself or his societal group, alter it. The unregenerate individual says to himself: it might be wrong when other people perjure themselves, steal, murder, or commit rape, but when I did those things, I had a good reason, and am therefore justified. Man can always reason out why their bad deed was not bad, but his neighbor’s was. Christopher’s brother Peter Hitchens, makes this point:

Left to themselves, human beings can in a matter of minutes justify the incineration of populated cities, the mass deportation – accompanied by slaughter, disease, and starvation – of inconvenient people, and the mass murder of the unborn. I have heard people who believe themselves to be good defend all these things and convince themselves as well as others. Quite often the same people will condemn similar actions committed by different countries, often with great vigor.[6]

You see, morality cannot be absolute and relative at the same time. We cannot say that the sense of good and evil it is innate in all of humanity, and at the same time, say there is no absolute source of that morality other than ourselves. If all morality is relative to the individual and to the individual’s culture, and there is no absolute standard for it set by God, the only way to determine right and wrong, good and bad, is ultimately by the sword. Might makes right, as they say. And why shouldn’t it? Why shouldn’t the unarmed give way to the lightly armed, and the lightly armed give way to the heavily armed?[7] Should not all societies, from the primitive to the advanced, decide for themselves what is right and what is wrong? Should not every individual decide for themselves their own religious beliefs (which is just another way of saying the same thing as morality)? This all sounds high minded and enlightened until you put it into practice. If what was just described was actually the type of world in which we lived, on what basis can one group of people condemn another group of people for, well, anything?

We look back at the Nazis and their systematic, state run genocide of the Jews and call it horrible. It was horrible. But on what basis can we condemn Nazi genocide of the Jews if there is no absolute truth that, “Thou shalt not kill”?[8] There is none. You may appeal to the innate sense inside of man that it is wrong to murder all you like; the Nazis would not call what they were doing murder. The only alternative that remains is that their actions were no better or worse than any other actions; we were simply stronger than they, and wanted to end their social, economic, and cultural system because it conflicted with our own, and so we did.

But it is wrong to murder people, especially on account of their race! Why? Says who?

Our culture takes a dim view of killing a person, generally speaking, unless one has a reasonable belief that one is in imminent danger of receiving great bodily harm, or death from them. In Nazi Germany, Jews were considered to be sub-humans, and therefore exempt from “normal” moral considerations. To turn a Jew in to the state, and thus mark him for persecution and death, was, in that society, to do a good work. But who are we to judge the society that has a different view of this matter? The National Socialists (Nazis) were quite deliberate in creating their society and culture, all based on the philosophical beliefs of Adolf Hitler. Are those beliefs, and the resulting consequences, not just as valid as our society’s contention that all men are created equal and endowed by their creator with inalienable rights? If you say they are not equally valid, you must answer why, and relative morality does not help your case. If you say they are equally valid, you are ignoring that impulse inside of mankind that does tell us that murdering another human being is wrong, and that we should do unto others as we would have others do unto us. It isn’t so much that religion gets it’s morality from man, as Christopher Hitchens contends; rather, the New Atheism, living as it does in the afterglow of the western Christian society, benefits from the fact that Judeo-Christian morality has served as the foundation for western society and culture and remains, for the time being, dominant and familiar to the vast majority of people.

In the afterglow of western Christian society, Peter Hitchens writes, where God’s moral standard served as the basis, it is convenient for the New Atheists to speak of an innate morality, which has its origins in man through evolutionary processes.[9] Morality is indeed imprinted on the heart of man. It is there because God put it there. It is His law, or at least a shadow of it; it convicts us of our sin when we transgress it, but it has no power to help us live up to its rigorous, unalterable standards. If we, as the New Atheists do, usurp God’s place as lawgiver, we become the one who sets the standard, if only in our own deluded mind. And, if we set the standard, we can change the standard. We can set the bar just high enough that it looks rigorous to other men. We can set the standard to define our behavior as good, and change it when we deem it expedient. We can do nothing, however, to hide our deficiency in living up to God’s moral standard from He, who is the true and only judge between right and wrong. We can only repent of our sins, because God has appointed a day on which He will judge the world in righteousness by the Man whom He has ordained. He has given assurance of this to all by raising Him from the dead.[10]

[1] Hitchens, Peter. 2010. The Rage against God: How Atheism Led Me to Faith. Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan.

[2] “Christopher Hitchens: The Morals of an Atheist.” 2007. Broadcast. Uncommon Knowledge. PBS. https://youtu.be/b6DW0e70DF0.

[3] “Christopher Hitchens: The Morals of an Atheist.” 2007. Broadcast. Uncommon Knowledge. PBS. https://youtu.be/b6DW0e70DF0.

[4] McCain, Paul Timothy., et. al., eds. 2005. Concordia: the Lutheran Confessions: a Readers Edition of the Book of Concord. St. Louis, MO: Concordia Pub. House. AC XCIII 1-9

[5] Hitchens, Peter. 2010. The Rage against God: How Atheism Led Me to Faith. Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan. p. 145.

[6] Hitchens, Peter. 2010. The Rage against God: How Atheism Led Me to Faith. Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan. p. 141-142.

[7] Hitchens, Peter. 2010. The Rage against God: How Atheism Led Me to Faith. Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan.

[8] In the Fifth Commandment, thou shalt not kill, God forbids us to take the life of another person, or our own life. This includes murder, abortion, euthanasia, and suicide.

[9] Hitchens, Peter. 2010. The Rage against God: How Atheism Led Me to Faith. Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan.

[10] Acts 17:31-32